In the controversy between the players and A.V. Lunatcharsky, Bolshevik Kommissar of Education in charge of the state theatres, which rent the peace of those institutions in Petrograd through the winter of 1917-1918, Meyerhold held aloof. He was extremely reticent in conversation concerning his political convictions, and I am not at all sure where his sympathies lie. While some of the leading artists refused to work under the new régime, Meyerhold went energetically about his tasks as régisseur as if there had been no change in governmental authority. If he chafed under the awkwardness of some of the new regulations, he was too shrewd to confess it. With his sensitive nature and his keen imagination, he combines a practical understanding of human affairs, and he knows that as the world runs today the artist should be happy if he is simply permitted to go ahead with his work, even if meddlesome officials of Tsar or of Soviet interpose in the matter of mechanism. [ Theatre Theatrical ]

«Actors work to all intents starts after the premier. I believe that a performance is never ready in premier. And that is not because we didn’t have the time to, but because it matures only in front of the audience». [Excerpts from an unpublished book of Alexander Glandov. Theatre Magazine, Vol.6. Greece 1962]

SHORT BIO: Meyerhold, Vsevolod Emilevich [1874-1940]

Russian theatre director, whose work inspired revolutionary artists and filmmakers of his era. He was born in Penza, Russia. In 1905 Meyerhold established his own studio, which promoted Symbolist plays, in which the actors moved like stylized puppets under the authoritarian controls of the director. Over the next decade, he experimented with improvisational, comic, and conventional forms of theatre, such as commedia dell’arte and Peking opera.

By the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Meyerhold was considered the leading avant-garde director in Russia. His most celebrated productions were eccentric and radical productions of Russian and European classics. Beginning in 1932 the Soviet regime under Joseph Stalin ended all forms of avant-garde innovation. In 1936 Meyerhold lost his theater, and four years later, after months of imprisonment and torture, the Soviet internal police secretly executed him.

The bio-mechanical system of Vsevolod Emilevich Meyerhold

can be defined not only as a system for the basic grounding of actors and stage

articulation, but also (although not quite finalised, is still well enough set out) of a global theatrical system. In connection with this, one should bear in mind the opinion stated by Aleksey Aleksandrovich Gvozdev, who, when speaking about a theatrical system, refers to it as the "relationship between dramaturgy, stage, actor’s performance

and the spectators." Coming in between the interaction of these four elements: stage

area, audience, actor’s performance and dramatic substance, followed by the theatre

director with his role as an innovative power to elevate all these elements, one can find

the main features of the creative work of Vsevolod Emilevich, and in the same scope, the

theory of biomechanics. Among the first theoretical and practical innovations which

Meyerhold introduced through his text as a theatre director, is the re-structuring of the

stage, deconstruction of the stage area and the abandonment of the concept of "a box

without the fourth wall". His reformation of the stage begins with the approach to

style, published during his period at the Theater-Studio. This stylisation leads Meyerhold

to the "arrangement of the stage with flat surfaces", specifically, to eliminate

the scenery and present the actor, as a pricipal mechanism for theatrical expression, as

the "setting". This is the beginning of the deconstruction of the stage space,

inherited from the old theatre, the theatre called by Aleksey Gvozdev "a theatre of

the Renaissance", which, apart from anything else, encourages the box-stage idea. The

de-structuring of the stage made Meyerhold take an interest in theatrical systems which

had abandoned the box-stage, more precisely, in the theater of the pre-Renaissance period,

mainly the Spanish theater, commedia dell’arte and, certainly, the ancient theater:

"If the Conditional theater prefers the destruction of decorations [...],

despises ramps [...], isn’t that theater leading to the resurrection of the theater

from antiquity? Yes, it is. The ancient theater, judging by its architecture, is a theatre

which contains everything necessary to our contemporary theatre: it has no decorations,

the space is in three dimensions. The ancient theater with its simplicity, with its

auditorium in the shape of a horse-shoe, with its orchestra, is a unique theater which can

be used for a varied repertoire: Fairground Booth of Blok, The Life of Man

of Andreyev, the tragedies of Maeterlinck...

The disarrangement of the

stage, which in practice began in the Theater-Studio, and which was theoretically

explained in the article "To the history and technique of the theater", had its

climax in the constructive solution of the The Magnificent Cuckold and The Death

of Tarelkin. The stage in these two performances not only resembles the renaissance

box, but is also made as dynamic as possible and put completely to the benefit of the

performance itself. It is stripped to the maximum extent, left with only enough elements

to enable the actor to convey his art. So, in the 20’s, Meyerhold’s dreams from

1912 finally came true, when he published To The History And Technique Of The Theater:

the props on stage are not mise en scene any more, but rather a supplement to the

actor’s body and movement. Thus, the wings of the windmill in The Magnificent

Cuckold rotate in strictly defined moments, actors vigorously pass through the

meat-grinding machine in The Death of Tarelkin, the stairs in the Cuckold

are a three-dimensional extension of the area used. The lighting is also subservient to

the arrangement of the stage area. Meyerhold is one of the first theatre directors of the

20th century who moved the lighting from the stage to the auditorium. In addition,

Meyerhold elevated the role of light and lighting to a level equal to the role of music

and rhythm in the performance. "The light should touch the spectator as does music.

Light must have its own rhythm, the score of light can be composed on the same principle

as that of the sonata."

The disarrangement of the

stage, which in practice began in the Theater-Studio, and which was theoretically

explained in the article "To the history and technique of the theater", had its

climax in the constructive solution of the The Magnificent Cuckold and The Death

of Tarelkin. The stage in these two performances not only resembles the renaissance

box, but is also made as dynamic as possible and put completely to the benefit of the

performance itself. It is stripped to the maximum extent, left with only enough elements

to enable the actor to convey his art. So, in the 20’s, Meyerhold’s dreams from

1912 finally came true, when he published To The History And Technique Of The Theater:

the props on stage are not mise en scene any more, but rather a supplement to the

actor’s body and movement. Thus, the wings of the windmill in The Magnificent

Cuckold rotate in strictly defined moments, actors vigorously pass through the

meat-grinding machine in The Death of Tarelkin, the stairs in the Cuckold

are a three-dimensional extension of the area used. The lighting is also subservient to

the arrangement of the stage area. Meyerhold is one of the first theatre directors of the

20th century who moved the lighting from the stage to the auditorium. In addition,

Meyerhold elevated the role of light and lighting to a level equal to the role of music

and rhythm in the performance. "The light should touch the spectator as does music.

Light must have its own rhythm, the score of light can be composed on the same principle

as that of the sonata."

Disarrangement of the

"box-stage" in the theatrical system inevitably includes another element, which

is very important to Meyerhold – the spectator. An imaginary wall of the room no

longer separates the stage from the auditorium. Actors do not play "as if they are

alone"; and they are supposed to be aware of the audience’s reaction at any

moment: "A specific peculiarity of the actor’s creativity (as opposed to the

originality of the playwright, the theatre director or the other artists) is that the

creative process is being conducted in front of the audience. As a result, the actor and

the spectator are interposing a particular mutual relationship, specifically, the actor

puts the spectator in the position of a sounding board, which reacts to every action upon

his command. And vice versa – sensing his own resonator (the audience), the actor

immediately reacts, by improvisation, to all the demands coming from the audience.

Following a series of signs (noise, movement, laughter etc.), the actor must define the

attitude of the audience towards the performance correctly." Thus, Meyerhold

contends, the goal will be achieved – "having control over the audience,

arousing even the most indifferent spectator’s emotions." The theatre director

must also think of the structure of spectators and their reactions while creating the

play: "A theatre director makes a great mistake if he does not take account of the

audience while preparing the play..." In order to fulfil this request, Meyerhold

thinks that "primarily, the spectator should be placed so that the rhythm of the play

can reach right down inside him." Therefore the proscenium, as the best way of

reaching this goal, is introduced. The proscenium of Vsevolod Emilevich is the bridge

between the stage and the auditorium, enabling the audience to infiltrate their emotions

into the play. The function of the proscenium, its redesign in fact, offered a new role to

the audience, and led to the final destruction of the box-stage. According to Vsevolod

Emilevich, the architecture of the Renaissance theater, by its separation from the

auditorium seats, balconies and boxes, does not correspond to the essence of theater

itself, since the spectator is set apart from the play. Furthermore, such separation is

not suitable because of the different angles from which the audience follows the events on

the stage. (This attitude, expressed in 1934, corresponds to the systems of a triangle-theater

and straight line-theater, mentioned by Vsevolod Emilevich in 1912. In the

triangle-theater, the spectator is outside the triangle, while in the straight

line-theater, the audience is already involved within the theatrical structure. Meyerhold

chose the straight line-theater, which offers many opportunities to the theatre director

to emphasize the temporary nature, as a natural feature of the scenic art). In order to

avoid separation of the audience from the play and at the same time, involving the

audience into the play, Meyerhold suggests, firstly, "disarrangement of the

box-stage. The first attack was made by those who extended the proscenium deep inside the

auditorium.[...] The new theatre [...] will have no box-stage; there is only the

proscenium, where the action takes place. In the ancient theatre, that place was called

the orchestra. The orchestra can have a circular, quadrangular, trianglular or

elliptical shape, it does not matter which. Its shape meets the demands of the

composition, as decided by the theatre director, as the creator of the whole

project.

The contemporaries of

Vsevolod Emilevich reacted noisily to his interpretation of the dramaturgical material. It

is the dramaturgical material, not the dramaturgy! It develops from the material

shaped by the theatre director according to his own needs, depending upon the imaginary

structure of the play and upon one’s own theatrical aesthetics. At this point, one

can see the serious disagreement between the attitudes Meyerhold held in his early years

to those of his mature ones. While in 1912, he considered that "the new theater

arises from literature", ten years later Vsevolod Emilevich had no time to wait for

the dramaturgy which corresponds to his theater, but "he takes over the initiative

himself and uses his own theatrical methods in order to imbue a new spirit into the old

body." With Meyerhold, the issue of which element had priority: drama text –

theater, simply does not exist. Everything is subordinated to the theatrical expression as

a whole. Therefore, without having any prejudice, in 1924 he dissects the play The

Forest by the classicist Ostrovsky into 33 episodes, thus abandoning all the

"rules of fine behaviour" and respect to Russian classical dramaturgy. Moscow,

as well as the whole of theatrical Russia was scandalized in 1926, finding Gogol’s The

Government Inspector, (sometimes titled The Inspector General) completely

changed. Meyerhold remodelled the Gogol’s comedy, deleting whole scenes, makes one

character out of two. The outcome was: Vsevolod Emilevich created a performance in which

there are only traces of Gogol; however, the theatre director Meyerhold is constantly

present. Vsevolod Emilevich, while analyzing The Government Inspector in front of

his theatre staff, says: "What makes this play difficult is that, like other plays,

it is directed towards the actor, not towards the theatre director." Meyerhold is

quite certain about who should manage the complex theatrical mechanism Therefore, the

Master, should "create (through changes in the text, amongst other things) a

situation which would be easiest for the actor, enabling him to put on the performance

without any difficulties." Such an approach gives the theatre director an opportunity

to model the text and adjust the dramaturgical material to his own theatrical and

aesthetic needs and principles. At the same time, the theatre director, while selecting

the play, is no more limited by the dramaturgic or literary values of the text. Simply, it

is possible to take low-quality dramatic material and re-arrange it. The limits, in this

case, are set only by the creative powers of the theatre director and of the actors.

The contemporaries of

Vsevolod Emilevich reacted noisily to his interpretation of the dramaturgical material. It

is the dramaturgical material, not the dramaturgy! It develops from the material

shaped by the theatre director according to his own needs, depending upon the imaginary

structure of the play and upon one’s own theatrical aesthetics. At this point, one

can see the serious disagreement between the attitudes Meyerhold held in his early years

to those of his mature ones. While in 1912, he considered that "the new theater

arises from literature", ten years later Vsevolod Emilevich had no time to wait for

the dramaturgy which corresponds to his theater, but "he takes over the initiative

himself and uses his own theatrical methods in order to imbue a new spirit into the old

body." With Meyerhold, the issue of which element had priority: drama text –

theater, simply does not exist. Everything is subordinated to the theatrical expression as

a whole. Therefore, without having any prejudice, in 1924 he dissects the play The

Forest by the classicist Ostrovsky into 33 episodes, thus abandoning all the

"rules of fine behaviour" and respect to Russian classical dramaturgy. Moscow,

as well as the whole of theatrical Russia was scandalized in 1926, finding Gogol’s The

Government Inspector, (sometimes titled The Inspector General) completely

changed. Meyerhold remodelled the Gogol’s comedy, deleting whole scenes, makes one

character out of two. The outcome was: Vsevolod Emilevich created a performance in which

there are only traces of Gogol; however, the theatre director Meyerhold is constantly

present. Vsevolod Emilevich, while analyzing The Government Inspector in front of

his theatre staff, says: "What makes this play difficult is that, like other plays,

it is directed towards the actor, not towards the theatre director." Meyerhold is

quite certain about who should manage the complex theatrical mechanism Therefore, the

Master, should "create (through changes in the text, amongst other things) a

situation which would be easiest for the actor, enabling him to put on the performance

without any difficulties." Such an approach gives the theatre director an opportunity

to model the text and adjust the dramaturgical material to his own theatrical and

aesthetic needs and principles. At the same time, the theatre director, while selecting

the play, is no more limited by the dramaturgic or literary values of the text. Simply, it

is possible to take low-quality dramatic material and re-arrange it. The limits, in this

case, are set only by the creative powers of the theatre director and of the actors.

Finally, we have reached the fourth basic element in the theatrical system advocated by Meyerhold: the actor. Prior to giving a resume of Vsevolod Emilevich’s attitudes about the actor and actor’s

play, we will briefly point to the specific relationship between the actor and the theatre

director in Meyerhold’s theatrical concept. Very often, at different times and at

different places, Meyerhold defines the actor as the main, fundamental element of the

theatrical performance. At first sight, such a definition is opposed to his proclaimed

attitude that the theater of Vsevolod Emilevich is a director’s theatre, a system

where the theatre director is the principal creator of the play. But only at first glance.

Specifically, since the actor is, to Vsevolod Emilevich, the central figure in the

theater, he is the only "medium" by which the theatrical director’s ideas

can be transmitted to the audience. Therefore, in one of his appeals, Meyerhold calls the

actors "living representatives of the theatre director’s idea." Certainly,

in order to be successful, the actor should have great natural creativity, in order to

convey the theatre director’s instructions through his own creative filter. According

to Vsevolod Emilevich, the task of the theatre director is "to sublimate certain

elements of the play, certain characters, each part, into an organic whole, suitable to

his own general idea of the complete play." On the other hand, the actor’s task,

while accepting some of the theatre director’s ideas about his character, is to

convey them through his own creative filter and transfer them to the audience. The main

issue in this piece of work is to study this transmission, namely, the manner of the

actor’s performance and the preparations for that performance.

Finally, we have reached the fourth basic element in the theatrical system advocated by Meyerhold: the actor. Prior to giving a resume of Vsevolod Emilevich’s attitudes about the actor and actor’s

play, we will briefly point to the specific relationship between the actor and the theatre

director in Meyerhold’s theatrical concept. Very often, at different times and at

different places, Meyerhold defines the actor as the main, fundamental element of the

theatrical performance. At first sight, such a definition is opposed to his proclaimed

attitude that the theater of Vsevolod Emilevich is a director’s theatre, a system

where the theatre director is the principal creator of the play. But only at first glance.

Specifically, since the actor is, to Vsevolod Emilevich, the central figure in the

theater, he is the only "medium" by which the theatrical director’s ideas

can be transmitted to the audience. Therefore, in one of his appeals, Meyerhold calls the

actors "living representatives of the theatre director’s idea." Certainly,

in order to be successful, the actor should have great natural creativity, in order to

convey the theatre director’s instructions through his own creative filter. According

to Vsevolod Emilevich, the task of the theatre director is "to sublimate certain

elements of the play, certain characters, each part, into an organic whole, suitable to

his own general idea of the complete play." On the other hand, the actor’s task,

while accepting some of the theatre director’s ideas about his character, is to

convey them through his own creative filter and transfer them to the audience. The main

issue in this piece of work is to study this transmission, namely, the manner of the

actor’s performance and the preparations for that performance.

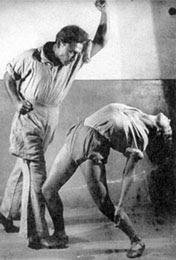

The biomechanics, conceived

by Vsevolod Emilevich, is simultaneously both a particular actor’s training and a way

of an actor’s performance, whose purpose is to effect the main request made by

Meyerhold on the stage, a request which he had made as early as 1905, in the theater

studio, and didn’t give up until his imprisonment in 1939: the flexibility of the

actor to convey his own creation through his body (consciously controlled!) and his

movements. "The creativity of the actor is shown in his movements, which are, through

the excitement, enriched by glare, colours and skills in order to stimulate the

spectator’s imagination." The biomechanic system, according to Meyerhold,

"is not a theatrical system, nor a specific kind of training; it is a part of the

exercises in the area of culture." However, this training is completely integrated

within Meyerhold’s theatrial system, requiring the actor to be a perfect machine

using the material performed in front of the audience – his body, to the utmost

limits: "The material of the actor’s art is the human body, i.e. the torso, the

limbs, the head and the voice. While studying his material, the actor should not rely upon

the anatomy, but upon the possibilities of his body, as a material for stage performance.

"

The biomechanics, conceived

by Vsevolod Emilevich, is simultaneously both a particular actor’s training and a way

of an actor’s performance, whose purpose is to effect the main request made by

Meyerhold on the stage, a request which he had made as early as 1905, in the theater

studio, and didn’t give up until his imprisonment in 1939: the flexibility of the

actor to convey his own creation through his body (consciously controlled!) and his

movements. "The creativity of the actor is shown in his movements, which are, through

the excitement, enriched by glare, colours and skills in order to stimulate the

spectator’s imagination." The biomechanic system, according to Meyerhold,

"is not a theatrical system, nor a specific kind of training; it is a part of the

exercises in the area of culture." However, this training is completely integrated

within Meyerhold’s theatrial system, requiring the actor to be a perfect machine

using the material performed in front of the audience – his body, to the utmost

limits: "The material of the actor’s art is the human body, i.e. the torso, the

limbs, the head and the voice. While studying his material, the actor should not rely upon

the anatomy, but upon the possibilities of his body, as a material for stage performance.

"

The biomechanical way of

training the actor’s body starts from the principles of tailoring the movements. The

theory of Frederick Winslow Taylor for rejecting all unnecessary movements during the

work, in order to reach greater productivity and effectiveness, and reduce the consumption

of physical power of the worker, corresponds to Meyerhold’s experiments in the

theater and to his searching for an actor who will respond to these experiments. "In

the work process, it is possible not only to distribute properly the rest period, says

Meyerhold in one of his speeches, but it is necessary to find such moments during work,

(Meyerhold’s italics – M. P.) which will thus provide the very best use of the

whole working time [...] This refers completely to the actor of a future theater."

The part which Meyerhold stressed in this declaration is, in fact an improvement of

Taylor’s theory. However, Vsevolod Emilevich, in his creative demands, cannot be

reduced to beeing a mere imitator of the thesis "man-machine", which was very

popular in Soviet Russia in the years after the October Revolution. It is quite clear that

he recognizes the actor as some kind of a machine (one of the principles of biomechanics

says: "the body is a machine, the worker is a machinist"), with a very important

correction – he lets the actor preserve creativity in his acting. That is the idea of

actor’s ambiguity. Specifically, starting from Coquelin senior, saying that the actor

is both a creator and a substance to the creativity, Meyerhold says: "It seems that

in each actor, when starting to play his role, there are two actors: the first one is

himself, the actor who actually exists and is ready to play the role on stage – A1,

and the second, who doesn’t yet exist, whom the actor is ready to send on stage

– A2. A1 looks upon A2 as material which still needs to be worked upon. Firstly, A1

should consider A2 within the stage area, since it is clear that the actor’s

performance depends greatly upon the size of the stage, its shape etc." Such a

structured concept of the actor’s technique is linked to the need for

"excitement", as a necessary element in the actor’s art. To Meyerhold,

"the excitement is the capability to convey an externally received task through

feelings, movements and words [...]. The co-ordinated demonstration of reflecting

excitement, in fact, represent the actor’s performance." The

actor-creator (A1 – using the terminology of Vsevolod Emilevich), quite consciously,

using his previous knowledge, capabilities, physical abilities and, of course, following

the theatre director’s own concept, shapes the material which is at his disposal --

primarily his own body. Up until now, the need for biomechanics and its principles,

primarily as a method of training for an actor, but also as a principle for stage

performance, has only been applied to its fullest extent in a couple of performances (in

the Magnificent Cuckold and in the Death of Tarelkin). From this point of

view, The Cuckold is, perhaps, the most extreme example of Meyerhold’s work,

but, as Vsevolod Emilevich says, "The Generous Cuckold" "was to

demonstrate the basis of the new technique of the play in a new artistic situation,"

particularly, to raise the actors’ performance to the absolute limits of the

experiment, to test in practice the theoretical surmises of Meyerhold and his colleagues.

Biomechanics, in a way,

raises these theoretical attitudes to their culminating height. Vsevolod Emilevich said,

"if the tip of the nose works – so does the whole body". This continues the

tradition of stressing the need for an actor "to observe himself" on the stage,

in other words, stressing (once again) the actor as one who synthesises both the creation

and the material from which that creation is made. This idea means that an actor has to be

capable of "co-ordinating in the space and on stage, the ability to find himself in

the whole course of the play, the ability to adjust and the ability to define visually the

distance between actors on the stage." The actor must have these qualities in order

to construct the whole performance in the best possible way and to give the theatre

director (the final sublimater of the creativity of all participants in the theatre) the

means by which to plan the development of the performance to the smallest detail.

One should bear in mind

that the whole concept of the actor’s performance, the introduction of biomechanics

into the theatre, is, as far as Meyerhold is concerned, only part of a constant effort to

define a theater which will go back to the roots of the theater, which will resurrect the

inherited dependence of the theatre, as a working principle. Whatever variety there was in

his creative work, whatever verbal inconsistencies and contradictions there may have been,

Meyerhold’s creative work has, over forty years, been directed towards one unique

goal: not to let theater be the same as life.

Translation: Evdokija Zafirovska

http://www.vor.ru/culture/cultarch57_eng.html#2

"... By 1938, Meyerhold must have known what lay in store for him. He spoke at the Director's Conference in June 1939, where he had an opportunity to recant or defend himself. From the reports of his speech, it appears that he had given up. The old spirit was gone.

Until 1991, the content of the speech was a matter of debate. From the best records available it is evident that he did not make the expected speech asking for the opportunity for greater creative freedom in what many thought was to be the new more tolerant climate of opinion, now that the worst of the show trials were over. Braun describes the speech:

"Tactically at least it made sense for him yo apologize for exposing"laboratory experiments" like The Forest and The Government Inspector to a wide audience. ..... Time and again, he approached such burning issues as the reinterpretation of the classics, the commanding role of the artistic director, the need to resist hack work, and the demand for a new heroic drama - only to lose himself in insignificant detail and inconclusive argument." (60)

The final blow came from the leader of the conference who summed up Meyerhold's defence:

The Party teaches us that it is not enough to merely admit our mistakes; we need to demonstrate their nature and their essence so that others may learn from them, above all our young people.....He said nothing about the nature of his mistakes, whereas he should have revealed those mistakes that led to his theatre becoming a theatre that was hostile towards the Soviet people, a theatre that was closed on the command of the Party. (61)

Shortly after his speech at the Director's Conference, Meyerhold was arrested and tortured over a period of a few weeks. In October,1939, he was indicted. Originally he was accused of being a Japanese and French spy based on the false confessions and accusations of tortured prisoners. Subjected to severe torture he signed confessions to acts he had never committed. His final indictment made the accusation that in 1930 Meyerhold was the head of the anti-Soviet Trotskyite group "Left Front', which coordinated all anti-Soviet elements in the field of the arts. He made appeals to repudiate his forced confessions concerning his links to foreign intelligence and with Trotskyite elements. In January 1940 he wrote a last appeal to Molotov concluding "I repudiate the confessions that were beaten out of me this way, and I beg you as Head of Government to save me and return me my freedom. I have my motherland and I will serve it with all my strength in the remaining years of my life. (62)

He pleaded not guilty to the charges but was sentenced to death on February 1. He was shot the following day in the cellars of the Military Collegium. It is reported that his last words were,"I am sixty-six. I want my daughter and my friends to know one day that I remained an honest Communist to the end." (63)His wife was found slaughtered by knife wounds in July 1939. He was officially declared a "non person". In 1955 he was rehabilitated, and since then his work has influenced a new generation of Russian directors.

Why did Meyerhold die an official "non-person" and Stanislavsky a "Peoples Artist". Given the irrationality of the Soviet era, searching for a rational explanation is futile and dispiriting. The despair under which these great artists were forced to live can only be compared to the control and oppression of the McCarthy era in Eisenhower America and the Nazi period in Hitler Germany, other times in which a perverted political logic prevailed. There were, of course, many reasons why Stanislavsky and Meyerhold were viewed so differently by the Soviet leaders in the 1930's. The most ostensible explanation is found in the different traditions they represented to the Communist aesthetic theorists. Stanislavsky was looked upon as the last disciple of the Russian realistic movement of the eighteenth century, which the Communist Party claimed as its own link to Russia's cultural past. On the other hand, Meyerhold represented the decadence of the detested bourgeois avant-garde and the Silver Age of St Petersburg. But this could hardly be the only reason for making an example of Meyerhold, and taking his life. Other practitioners of the avant-garde such as Tairov were allowed to recant and were spared. One could speculate on some of the darker subterranean social and psychological reasons underlying Meyerhold's unpopularity. There was the animosity he created among his theatrical colleagues who deserted him in the end. Their lack of loyalty could be explained by his dictatorial manner, his frequently articulated attitude about the secondary place of the actor as opposed to the director, his arbitrariness and his favoritism in awarding roles to his wife, Zinaida. (64) Part of the reason undoubtedly had to do with his uncompromising and difficult nature. He left the Moscow Art Theatre because of difficulties with the management; he sued Vera Komissarzhevskaya after he was forced to leave her troupe over artistic differences; he resigned from his post at the Theatre Section under Lunacharsky; and his relationship to the personnel at his own theatre in its last days were very strained. Stanislavsky, on the other hand, was expert at adjusting to the organizations he was involved with. He stayed on with the family firm after entering the Moscow Art Theatre. He weathered many arguments with Nemirovich while at the Art Theatre. He behaved civilly to, Heitz, the Communist imposed director of the Art Theatre during the late twenties and even could engage in civilized correspondence with Stalin.

Some of the reasons for their respective treatments by the Soviets are of a more pragmatic and partisan political nature. There were the mistakes Meyerhold made in forging early connections with the Trotskyite element of the Bolshevik Party as opposed to Stanislavsky's lack of partisan connection to the Party; Meyerhold's steadfast commitment during the 1920's to his anti-realistic theatrical style as the style of the Revolution as opposed to Stanislavsky's malleability in adapting his naturalistic realistic style with roots in the realistic Golden Age of literature and art in the eighteenth century to the approved Soviet repertory of the 1930's; Meyerhold's untiring energy and stubbornness that would not allow him to recant or go back on principle as he saw it, until it was too late, as compared to Stanislavsky's weakened condition late in life that sapped him of his energy and put him in a position where he was under constant surveillance and in the end under complete control of Stalin by 1932; and, finally, Stanislavsky's ability to create a theatre organization and a method of training actors and directors that could be easily taught and made into a tradition capable of supporting socialist realism opposed to Meyerhold's creative methods that were uniquely individualistic and defied easy codification. From the Party's point of view, if there were to be a Soviet style it would more naturally be Stanislavsky's realism, and if there was a theatrical person whose relationship to the Party was to be emulated it was Stanislavsky. Under the twisted logic and extreme paranoia of Stalin and the Communist Party late in the 1930's Meyerhold was indeed "an enemy of the People". Even if he lived up to his last minute promises to change, he could not be used by the Party to further its goals of cultural and economic subservience. He was more valuable to Stalin as a terrible example of what could happen if the Communist Party was not blindly obeyed. He was a perfect illustration of the spirit of freedom of the 1920's, which Stalin was trying to eradicate by force and intimidation. Stanislavsky and his theatre were totally under the government's control in Stanislavsky's last years, the control that Stalin would like to have had over all of Russian society. Stanislavsky and his methods could be manipulated by Stalin and the Party. From the government's point of view he was valuable asset and could be set up as an example for others in the arts, a true "An Artist of the People. Giving Meyerhold the new theatre, which was being constructed for him and allowing him to rebuild his reputation would not have been in the best interest of the Party, unless they could be sure he could be controlled. Given Meyerhold's past history this was extremely unlikely.

When Stanislavsky died tributes flowed in from all over the world. His acting method was made the catechism for the Russian theatre. His grave is in the cemetery of the Novodevichy Monastery where the Russian great are buried, near Chekhov's grave in that corner of the graveyard reserved now for members of the original Moscow Art company. But Meyerhold is not buried there. His ashes were deposited in the cemetery of the Don Monastery, together with those of almost 500 other victims of the Soviet purge era in "Common Grave No.1" which bears the inscription: HERE LIE THE REMAINS OF INNOCENT VICTIMS OF POLITICAL REPRESSION WHO WERE TORTURED AND SHOT IN THE YEARS 1930-1942 TO THEIR ETERNAL MEMORY."

http://rutheater.home.att.net/stana.htm

"Repression and political control have long been part Russian theatrical life. (65) The control by the Soviets of theatre for most of the twentieth century may be looked on as part of a continuing Russian tradition, not a aberration. In the 1670's when Alexia Mikhailovich, the second tzar of the Romanov dynasty, brought German actors to the Russian court to train Russian performers, the tradition of political control of the theatre was established. Later Peter the Great used the theatre to educate and refine the crude Russian princes of his court. Catherine the Great wrote plays to communicate her ideas of the ideal social order. The lesser monarchs of the nineteenth century, who had to deal with a theatre catering to the middle class, more crudely controlled the theatre through the power of censorship. Control was always from a central authority and repression was part of theatrical life, in both the aristocratic court theatre and the theatre of the middle class. The serf theatre, the only theatre not under state control flourished from the end of the eighteenth century to 1861 also existed in a climate of repression. Even when Alexander as part of his liberal reforms allowed commercial theatres to be formed in 1882, the theatre was closely watched by his censors for their political and ideological content. Such was the climate until the October Revolution of 1917. The decade after the revolution, was rare, a period when experimentation was tolerated. But in 1928 with the coming of Stalin's five year plans, repression again became the order of the day. By 1936 the repression had hardened into the orthodoxy of "socialist realism". The period from the beginning of the century until the mid-nineteen thirties with the lifting of oppression, the Revolution and the Civil War, and the post war experimental policies of Lenin, saw a powerful outburst of artistic, political and social energy resulting in unprecedented change in Russian society and the flowering of a Golden Age of Russian theatre, whose vitality and accomplishment were to affect the Western theatre for the remainder of the century. And Stanislavsky and Meyerhold were both victims caught in the cross fire of opposing forces which characterize this period. How ironic it is that these two men driven primarily by artistic concerns were to have their fates decided primarily by political forces.

Stanislavsky was the great innovator of the pre-Revolutionary era. His work as a director and acting theorist may be considered the theatrical culmination of the Russia's Golden Age of Art begun in the mid-nineteenth century, combining realism with a progressive social message. He was a descendent of Gogal, Ostrovsky, Shchepkin, and Tolstoy - an artistic heritage manipulated,distorted and made grotesque by the socialist realists in the 1930's. He was able to achieve great artistic heights in an era of alternating lifting and pressing of tzarist oppression at the beginning of the century. His art was an art of subtlety and nuance. He and his artistic theories were able to survive under the Imperial,the Revolutionary and the Soviet systems.

Meyerhold, the great innovator of the 1920's, brought to fruition the goals of the Russian aesthetic movement begun in the 1890's, Russia's Silver Age of Art. An aesthetic movement begun in mysticism and comfortable with theatricality. The tradition of the poet and critic Merezzhovsky of the in the early 1890's, Briussov and other early Russian Symbolists, and Diaghilev and the World of Art Movement in the late 1890's. He carried the St Petersburg aesthetic of the first decade of the century into the Soviet period.

Meyerhold thrived in the brief NEP period in the early 1920's when economic,social and artistic innovation were encouraged, albeit within an the emerging repressive Communist political system. And Meyerhold's approach to life and art was bold. This was his period of greatest success. The times promised to reward boldness, but finally did not.

In the Soviet theatre of the 1930's, commitment to the ideals of the Revolution was not enough to guarantee success or even survival. Total devotion and slavish adherence to the Party was demanded in artistic as in all other aspects of life. Meyerhold embraced the Revolution and Stanislavsky adapted to it, with ironic results.

Stanislavsky and his artistic theories based on the aesthetically conservative tradition of Russian realism were manipulated by the Stalinists - his theatrical theories corrupted. In its pure form Stanislavsky's realism attempted to allow the audience to get to the "inner reality" beyond the stage action. In its Soviet socialist form, realism heavy- handedly presented and propagated a distorted and limited reality. The Soviet theatre was a conservative theatre posing as a revolutionary theatre.

Meyerhold's theatre, based on twentieth century thought and theories of art, looked to a new future and was truly revolutionary. It looked to old theatrical forms for its inspiration, and in execution created new theatrical forms. Traces of Meyerhold's spirit is still to be found in the avant-garde theatre of the 1990's in Russia and throughout the West. Because it required a social system permitting complete freedom of expression, this theatre could not survive the Soviet totalitarian regime. It was a director based theatre encouraging innovation in style and content. Distortion of an author's intention or of reality itself was permitted and encouraged. His theatre demanded freedom to create a theatrical reality representing the personal and unique vision of the director. Theatre which would allow the audience to see reality anew and perhaps create its own reality. This was a freedom which the Soviets could not allow. The Soviets could not manipulate Meyerhold's ideas for their own purposes.

In the end, Meyerhold who embraced the Revolution became, a victim of it. Stanislavsky who never became a Party member became its theatrical patron saint."

[ Stanislavsky, Meyerhold and the Politics of Their Time ]

"For Russians, Theater Is a Process of Constant Rediscovery" NYT -- http://rutheater.home.att.net/russians.htm (2001?)

[

I want to burn with the spirit of the times. I want all servants of the stage to recognize their high destiny. I am irritated by those comrades of mine who have no desire to rise above the narrow interests of their caste and respond to the interests of society. Yes, the theatre is capable of playing an enormous part in the transformation of the whole of existence! ~Meyerhold (Braun 159)

I want to burn with the spirit of the times. I want all servants of the stage to recognize their high destiny. I am irritated by those comrades of mine who have no desire to rise above the narrow interests of their caste and respond to the interests of society. Yes, the theatre is capable of playing an enormous part in the transformation of the whole of existence! ~Meyerhold (Braun 159)